Floating cities could ease the world’s housing crunch

LONDON: This week dozens of experts, investors, scientists, and officials—along with a group of students on a video link from Nairobi—explored a new approach to building offshore hubs of habitation, commerce, education, and recreation designed to ease pressures facing coastal cities squeezed between rising populations, rising seas and storm risk, resource limits, and threatened ecosystems.

Bright and dark visions of humanity spreading from land to life offshore have been around for decades, with variants ranging from hopeful—a vaulting pyramid-shaped floating city conceived for Tokyo Bay in the 1960s by R. Buckminster Fuller—to involuntary, as with straggling survivors of a flooded planet building ragtag “atolls” in the dystopian 1995 film Waterworld.

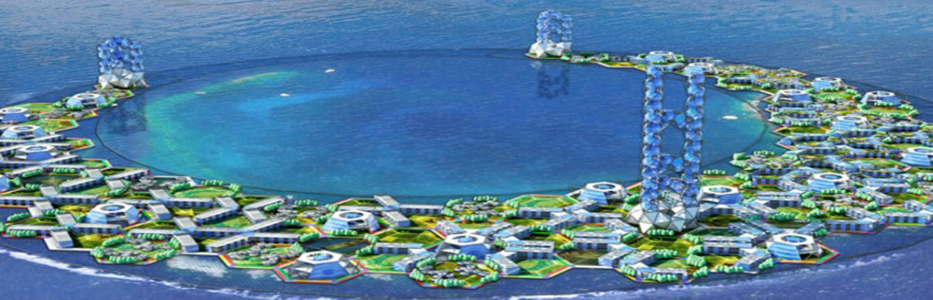

They envision an eventual galaxy of satellite “cities” built where coastal urbanization is hitting limits. They would consist of mass-produced, storm-worthy hexagonal floating modules, towed into position, moored and connected in larger arrays topped by sustainably built housing, workplaces, recreational and religious facilities, and the rest. Ferries and drones would be a tie line to shore. The communities would be sustained as much as possible with local solar and other renewable energy, recirculating water and rainwater, and local food production.

At first hearing, the concept of floating cities has the feel of magical thinking.

But coastal cities around the world face the ultimate space crunch, and it’s worsening fast.

The erosion of polar ice sheets and expansion of heated seawater under global warming are relentlessly raising sea levels, almost assuredly for centuries to come, with only the pace of coastal immersion, and rising storm-surge losses, in question. And coastal risk is building even faster through the surge in populations in a fast-urbanizing world.

So it would be magical thinking to exclude such solutions, proponents say.

The project is the brainchild of Marc Collins, a Hawaiian-born entrepreneur with Tahitian and Chinese family roots who has spent more than a decade pursuing a range of options for such developments, including ones favored by “seasteading” individualists seeking to escape the strictures of governments and taxes.

In interviews, he said he came to realize that floating communities can only really succeed with government support and would work best within a country’s coastal waters. “It will take governments,” he said in an interview.

This proposal is aiming for a middle ground, attracting investors by centering on Asia—where cities are extraordinarily dense and real estate exorbitantly pricey, and where there’s substantial government power to orchestrate offshore or onshore development. But Collins said it’s vital that such projects benefit everyone in a city, not just the prosperous. “This can’t turn into something where a bunch of rich people watch poor people drown on the beach,” he said in an interview.

The meeting was hosted by the UN-Habitat program, which was launched in 1978 to pursue progress toward socially and environmentally sound human communities and is now focused on achieving Sustainable Development Goal 11, making cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable by 2030.

It’s not an agency associated with cutting-edge technology or design. But given the intensifying pressures, particularly the slow progress addressing human-driven global warming, unconventional solutions can no longer be discounted, said Victor Kisob, deputy executive director of UN-Habitat and the convener for the day.

How did such an unconventional idea take center stage?

“This got into the mix simply as we looked at possible solutions out there that we could consider when you have a superstorm Sandy or the humanitarian crises we’re dealing with, as in Mozambique,” he said. “Listening to Marc and seeing his designs, this seems futuristic but it really is practical. And you have to consider what would happen to these places otherwise.”

During the course of the day, the merits of such a project, in theory, became evident. The threat from rising seas and storm surge is erased a mile or two offshore. Even tsunamis would not pose the kind of threat they pose to coasts because such quake-triggered waves only rise to devastating heights in shallowing waters.

Offshore waters can be leased in most countries for dollars an acre while real estate values in cities like Hong Kong or Lagos are astronomical.

But the discussion identified a wide array of issues.

Some were technical. Can a cluster of tethered, moored platforms ride out a typhoon?

Nicholas Makris, the director of MIT’s Center for Ocean Engineering, was on hand with several colleagues. He asked how many attendees had been at sea in hurricane-strength winds. Only his hand went up.

Makris described a host of structures around the world designed for such conditions, but noted they are all enormous, and enormously expensive, components of global oil and gas infrastructure.

In an interview, he said the Oceanix concept has merit, but would need to be restricted to sheltered waters as designed.

Scale of course is perhaps the grandest challenge. There are plenty of floating structures around the world now. The low-lying Netherlands, long in the lead on such efforts, has a prototype floating dairy farm in Rotterdam, and is home to a new Global Center on Adaptation to climate change—housed in a floating building. But the farm is designed for 40 cows.

But Collins notes that the Oceanix concept centers on eventual mass manufacturing of the basic floating units, which can then be towed anywhere in the world, offering the same economies through manufacturing efficiency that so deeply cut the cost of everything from furniture to solar cells.

While the construction of such communities can be expensive, he said, an Oceanix “city” would be a bargain compared to the cost of housing onshore. And the societal value can be enormous in the world’s fastest-growing cities, where housing shortages and costs place a particularly enormous burden on the poor.

Enthusiasm was expressed at the meeting by Joseph Stiglitz, the Columbia University Nobel laureate in economics who has built his career on studying policy paths to reducing inequality. “It’s certainly worth trying,” he said in an interview. “The only way you’re going to find things out is to actually do these things.”

He said the merit of moving offshore is the capacity to start from scratch, taking a holistic approach to shaping services and limiting costs and risks—both environmental and financial.

The meeting also identified political and social challenges.

How would residents of these communities be chosen? Students in the video link from Nairobi were less focused on the technology than on doubts about how such projects would lessen the world’s rich-poor divide.

One observer in the seats fringing the central circular table wondered whether young people might feel isolated on such an artificial island, even connected by transportation to the coast. From Polynesia to North Africa, the allure of cities worldwide is magnified for the young, not only for jobs but also for arts, culture, creativity, connection.

Would island living be seen as a trap?

But another young person, Max Kessler, an engineering student from MIT, said he was eager to work on this kind of project.

“I grew up on an island in the Pacific Northwest,” he said. “If we create something that can foster the kind of tight-knit culture and mentality of sustainability we had there, this is really doable.”

Another participant noted that the community design would be ideal for the elderly, offering an important option for retirement housing as the percentage of elderly in populations swells in coming decades.

Urbanization and development are all about tradeoffs. If an option like floating annexes doesn’t take hold, that could simply boost the prospects for more dredging and filling—the solutions of choice through the past century, which already say global sea levels rise about a foot.

The island nation state Singapore, through sand mining and imports and filling has expanded its size by almost a quarter since independence in 1965, according to the United Nations. But the environmental damage from the global sand industry and from the filling is limiting that option going forward.

It’s no surprise, then, that later this month Singapore is holding a more expressly commercial event promoting offshore development—the World Conference on Floating Solutions.

Before the day was out, the idea gained a remarkable endorsement from Deputy Secretary-General Amina J. Mohammed, who had dealt with excruciating coastal challenges as Nigeria’s environment minister, particularly in another kind of floating city—Lagos’s vast offshore Makoko slum, where several hundred thousand people live in a maze of tethered boats and rafts.

She said it would take years, but perhaps this floating-community model could help there. “We really do have an opportunity to do something” in places like Makoko, she said. “We could take from our universities, young people, partners from outside, and turn this into a shining example of the possibilities for millions of people being able to live on a coast and not have to move inside if they didn’t have to.”

She said “frontier” ideas and innovations are essential as the world grapples with achieving sustainable development amid accelerating environmental and technological change. (In May, another United Nations branch will hold a Geneva session on the role of science and technology in accelerating progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals.)

“Our approaches to development and environmental sustainability in cities need a serious retooling to meet the challenges of today and tomorrow,” Mohammed said, noting that cities are the main testing ground for new ideas and noting the urgency of climate vulnerability. “Floating cities can be part of our new arsenal of tools.”